Inscription Rock – El Morro NM

I was going to write up some data for this location when I stumbled across this article written as part of a brochure for Inscription Rock. The article tells it all much better than I could. Make sure you hike to the top for the pueblo dwellings and great scenes. I stopped because I had read about Beals camels across the desert.

The article discusses:

Who did that?

What happened?

Where did it take place?

When did it take place?

Why did that happen?:

El Morro National Monument

History on a rock

Text and Photos By Joann Mazzio

In western New Mexico, bordering on the Ramah Navajo Reservation, a castle-like natural rock formation looms from the surrounding plateau of scrubby desert plants and junipers. Gathering a few ponderosas on its skirts, the sandstone bluff juts 200 feet above the surrounding land. This is El Morro, where history is written with permanence found on the old civilization monuments in the Near East, telling of the battles of ancient kings.

At the base of the bluff – often called Inscription Rock — on sheltered smooth slabs of stone, are 7 centuries of inscriptions covering human interaction with this spot.

This massive mesa point forms a striking landmark. In fact, El Morro means “the headland.” From its summit, rain and melted snow drain into a natural basin at the foot of the cliff, creating a constant and dependable supply of water. The pool attracted coyotes, deer and other wild creatures. A pre-Columbian route from Acoma and the Rio Grande valley to the Zuni pueblos led directly past El Morro, probably marking it as a favored camping site for prehistoric travelers.

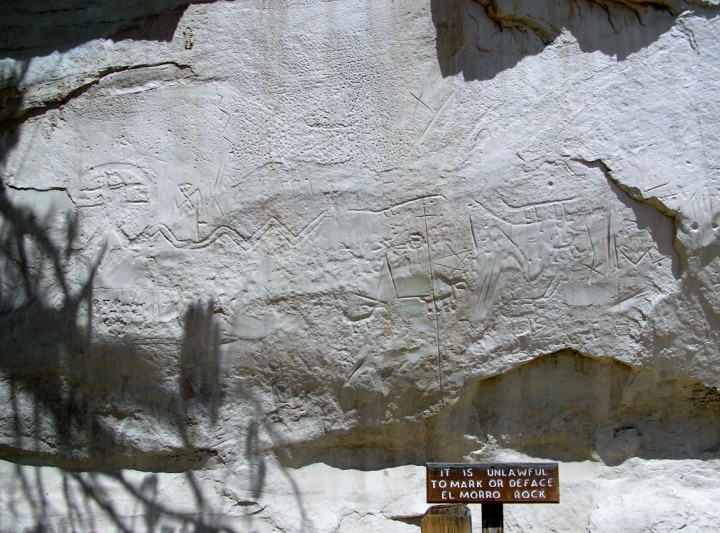

On the top of El Morro, in the late 13th century, people built an 875-room pueblo, so inaccessible to outsiders as to rival Acoma. After only a couple of generations they moved out. But, they and travelers, left petroglyphs — pecked-out outlines of bear tracks, human hands, and other symbols on the creamy sandstone wall.

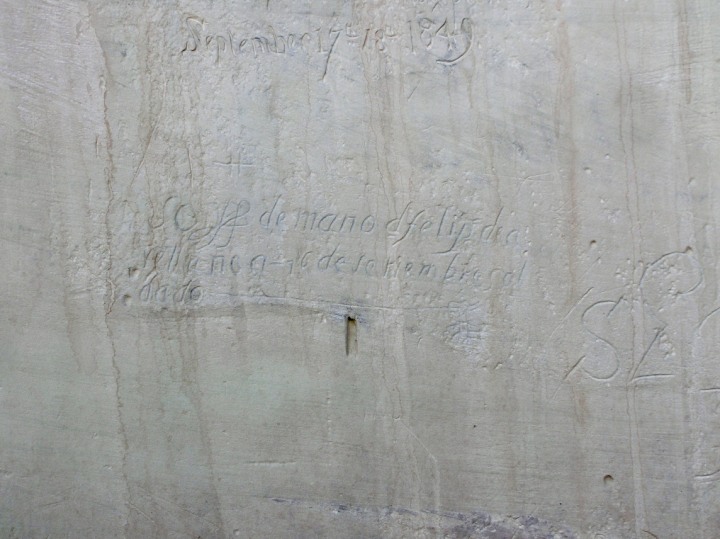

Then the Europeans came. El Morro was as much a landmark and water source for the conquistadors as for the natives. The first known historical mention of El Morro is found in the journal of Diego Pérez de Luxán, chronicler of the Espejo Expedition, which stopped at the landmark for water on March 11, 1583. The words “Pasó por Aqui” begin the first Spanish inscription, a message left by Don Juan de Oñate, the first governor under Spain, of New Mexico. Translated, it reads, “Passed by here the Governor Don Juan de Oñate, from the discovery of the Sea of the South on the 16th of April 1605.” Despite the elegant, careful carving of this pronouncement, some historians now think the explorer did not actually reach the Gulf of California, as it is now known. Oñate went by here several times mostly trying to recoup the personal fortune he invested in leading expeditions from Mexico to colonize New Mexico.

In 1680, the great Pueblo Indian revolt drove the Spaniards from New Mexico. More than 400 lost their lives, including 23 priests, and the remainder fled to El Paso. Twelve years later, Don Diego de Vargas restored order without further bloodshed.

It is no wonder that de Vargas, the most famous governor of New Mexico, seems boastful in the message he left at El Morro. Translated, his words read, “Here was the General Don Diego de Vargas, who conquered for our Holy Faith and for the Royal Crown all of New Mexico at his own expense, year of 1692.” At this time, the province of New Mexico extended roughly from the border of Louisiana to the border of California, making the history recorded on El Morro the history of a vast region.

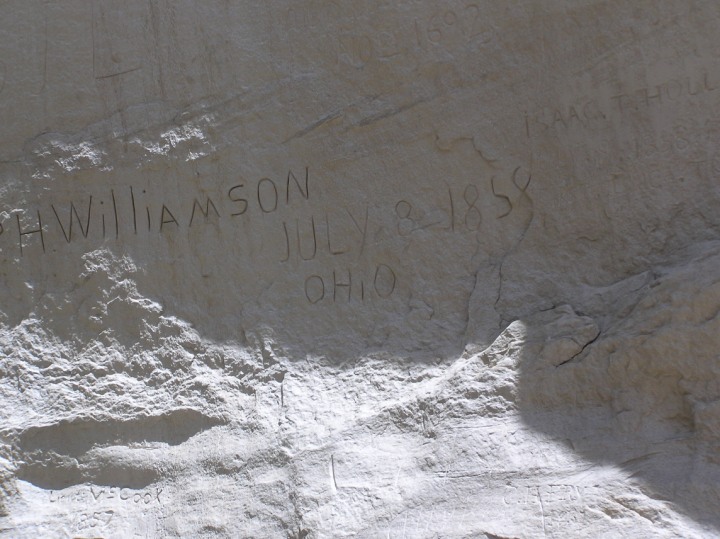

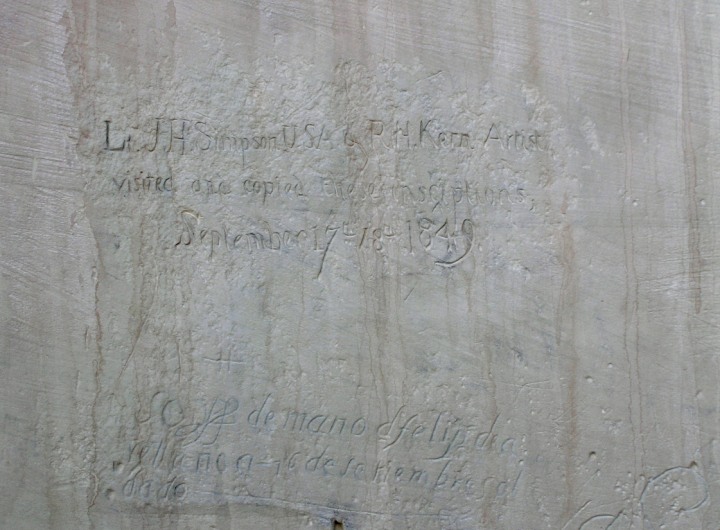

The army of General Stephen W. Kearny occupied Santa Fe in August 1846, and details of US troops were dispatched to explore various parts of the territory. Probably the first American officer to visit El Morro was Lieutenant J.H. Simpson, accompanied by the artist R.H. Kern, who copied some of the early inscriptions in September 1849.

Some of the most gracefully carved of the inscriptions were made on August 23, 1859, when an Army expedition led by Lieutenant Edward Beale passed through, establishing a new route from Texas to California. This group included 25 Egyptian camels being tested as pack animals, an idea that came to nothing. Their wrangler, P. Gilmer Breckinridge, also left his signature on the rock.

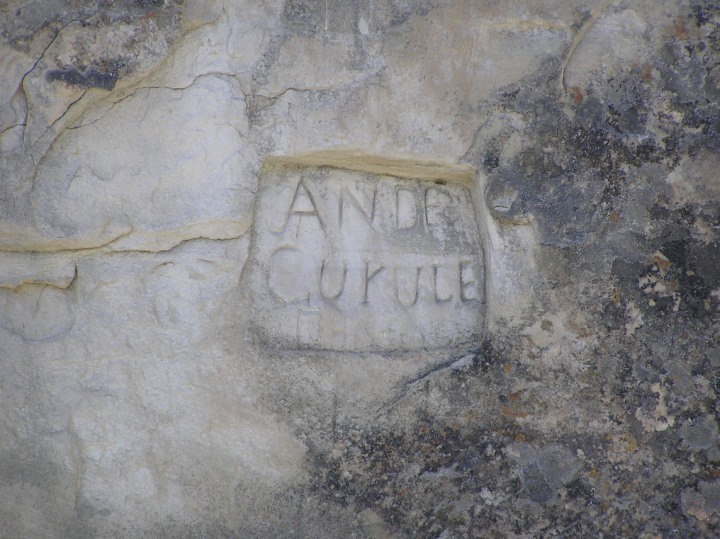

The names of other soldiers, Indian agents, surveyors, emigrants traveling westward, and settlers were added to the rock. So many travelers added their names and messages that by 1906, El Morro’s historical significance was dwarfed by the graffiti-like excess that marred the walls and overlapped some of the older inscriptions. In that year, the site was proclaimed a National Monument.

Imagine, if you can, on the East Coast, a naturally occurring megalith rising from the flat land of Florida. In addition to the petroglyphs of prehistoric inhabitants, this rock wall has on it messages inscribed by members of the parties of Christopher Columbus, Juan Ponce de Leon, and Andrew Jackson as they passed by. Such a historically significant monument would rank in United States history right alongside Plymouth Rock.

By contrast, El Morro faded into the backwaters of Southwestern history when the railroad line was built 20 miles to the north. El Morro’s water supply was no longer needed. For many visitors, however, there are still lessons in history to be learned from a trip to El Morro.On approaching, it is reassuring to see the sandstone massif rise as a landmark, just as it did for earlier travelers. An easy, one-half mile, self-guided walk brings a visitor to the pool and inscriptions. The calligraphy of messages from the 1800s is appealingly dated. From the prehistoric past though, the handprints leap out, calling for human touch, human contact. (Don’t respond. The inscriptions are already being eroded away by natural causes.) On a summer day now, the shade furnishes an oasis against the desert sun just as it did long ago.

A more strenuous two-mile hike winds up the sides of the bluff, leading to the top and a view of a box canyon enclosed by El Morro. Across the top of the bluff are remnants of unexcavated and excavated pueblo dwellings, kivas and other structures. From here, a visitor now can look out at today’s landscape, but can also look into the past. Perhaps the imagination will stir up the dust of a thirsty caravan coming from the east, the oxen straining against their heavy wooden yokes, the tired horses surging forward to the promise of water.

Getting to El Morro – From Grants, NM, on I-40, take NM-53 west, past El Malpais National Monument to the El Morro National Monument turnoff. Visitor center is open daily (9am to 7PM in summer; to 5pm in winter) except Christmas and New Year’s. Trails close one hour before the visitor center. For more information call 505-783-4226.