Photos by Joan and Mike Sinnwell September 2012

Granite Montana Ghost Town

Hector Horton first discovered silver in the general area in 1865. In the autumn of 1872 the Granite mine was discovered by a prospector named Holland. Eli Holland is said to have found a piece of high grade ruby silver while following a wounded game animal (deer or elk) in 1872. A shallow shaft was dug on the outcropping. Nothing was done at the site for over five years until Charles McLure found a piece of the silver ore on the shaft dump and thought the prospect showed promise. He traveled east to St. Louis where he obtained capital to begin exploration and development of the property.

The mine was relocated in 1875. This was the richest silver mine on the earth, and it might never have been discovered if a telegram from the east hadn’t been delayed. The backers of the mine thought the venture was hopeless and ordered an end to its operation, but the last blast on the last shift uncovered a bonanza, which yielded $40,000,000.

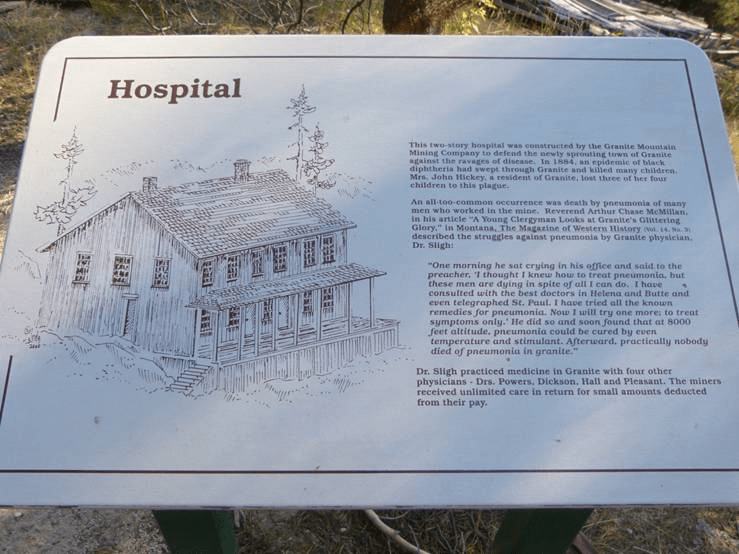

The town of Granite was established in 1884. Nicknamed “Montana’s Silver Queen,” Granite had its heyday in the early 1890’s. The town eventually became a thriving city which boasted as many stores and commercial establishments as any other modern city at that time in Montana. One of the most famous buildings in Granite was a large Miner’s Union Hall with a pool parlor and club area on the first floor and an office, a library, a large dance floor, and an auditorium space on the second floor. The second floor was called the “Northwest’s Finest Dance Floor.” Quite often the auditorium played host to mineral shows, melodramas, and vaudeville. Some of the other amenities Granite offered were 18 saloons, a thriving red light district, a roller rink, a hospital, five doctors, a school, four churches, several banks, a water system, named streets, and several homes for the more than 3,000 inhabitants. However, there was no cemetery. All of the bodies were interned in the Philipsburg Cemetery because the ground was so rock infested in Granite that a grave was hard to dug.

In the silver panic of 1893, word came to shut the mine down. The mine was deserted for three years, never again would it reach the population it once had of 3,000 miners. In 1893, the U.S. Congress repealed the Sherman Act resulting in lower silver prices, and on the morning of August 1, 1893, within 24 hours of the repealing the act, many men, women, and children came down the mountain in search of new homes. Because of the swiftness of the move, most of their worldly possessions remained on the hill behind them. Only 140 people remained in Granite one year later, in 1894.

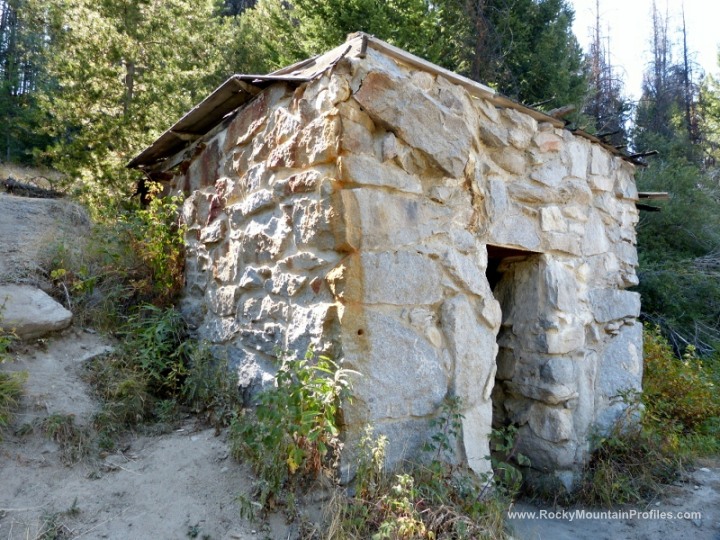

Today there is no one living in the camp. The shell of the Miners’ Union Hall still stands.

Sometimes disappointment sets in when you visit a site. It is obvious that a lot of hard work was put in to post signs, provide a walking tour, build trails, post maps and preserve the site only to be vandalized. Even so there is still much to see. Make sure you look closely on the drive to the site as you can see remains of the hospital, wooden towers for the old tramway and the remains of numerous cabins etc. Here is an example of one of the remaining signs that has not been destroyed. Make sure to read the story.